Review: ‘Encanto’ uses magic realism to reflect on reconciliation and tradition

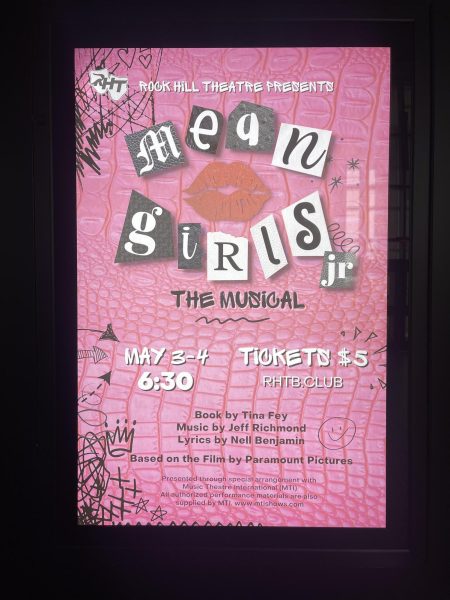

A promotional poster for “Encanto,” which premiered on Nov. 24, is displayed inside a local movie theater. The movie’s themes focus on family, tradition and belonging in accordance with typical end-of-the-year spirit. Staff writer Nanditha Nagavishnu reviews the movie, saying its “flowery color palette and rosy soundtrack” make it a fun watch.

Disney’s new movie “Encanto” was released in the middle of Thanksgiving week, timely marketing for a story exploring ideas of family, love and the security of tradition. Its success isn’t surprising, with posters and scenes highlighting the film’s flowery color palette and rosy soundtrack.

Seemingly set in Colombia, though there isn’t much historical or situational context except for montages of the Indigenous community being chased from their lands by horse-straddling white men. The movie makes a conscious effort in representation by adding Latinos of all colors and hair textures and refraining from stereotypical gender roles, sometimes actively putting female characters in traditionally male roles as with the wrestler-built Luisa.

In a cathartic scene, Luisa even sings about her vulnerability and the debilitating nature of responsibility. Although she is physically strong, she shouldn’t be expected to have only stable moods. This is usually a trope applied to show pent-up masculinity. It is refreshing to see characters that stand on their own merits and insecurities separate from the limitations of representing a minority race or gender.

Essentially, “Encanto” is about appearances and apparent happiness and coherence deception. We revolve around the Madrigals, an odd family housing dynamic relationships. The Madrigals are the most prominent family in a community grown close through shared oppression. All family members have a unique magical ability except for our protagonist, Mirabel. Magic is the family’s pride, and Mirabel has to balance feeling like an outsider because of this lack and being filled with overwhelming pride for her family’s heritage.

An interesting dynamic is between Mirabel and her sister Isabella, whose magical ability is essentially being “perfect” and creating flowers. However, she resents Mirabel because of her unruliness, and Mirabel resents her vanity, making the progression of their relationship sweetly instructive. At one point, Isabella sings, “I’m so sick of pretty, I want something new,” vocalizing her desire to be understood for her insecurities and whims rather than an aesthetic.

Other abilities in the Madrigals include shapeshifting, rain clouds and talking to animals, all convenient and straightforward. It might seem tempting to accuse the production of trivializing the more nuanced concept of magic in Latin American tradition, but this is almost made up for when the film admits magic’s dangers and healing capacities. It is conscious of telling us that the family just “lost sight of [what their] miracle was for.”

The magic in “Encanto” is featured as a positive spirit, giving the community and the family something to be proud of and stable in their shaky concept of home resulting from displacement. This general cheer surrounding the movie makes it very festive and suitable for the end-of-the-year spirit. Conscious of this, they include a member whose ability is food that heals wounds, evoking the connotations around Thanksgiving food.

The central conflict is the slow disappearance of their magic, and Mirabel becomes the protagonist in a story about uncovering old secrets and fixing the familial bond. For the Madrigals’ matriarch, Mirabel’s grandmother, the magic is her sanity, her source of pride, without which deep insecurities and wounds surface. She is even distant toward Mirabel because she sees her as average, a tear in the family legacy. Still, you can feel that no other Madrigal is as proud and protective of the family’s gift as Mirabel, who copes with feeling like an outsider in her own home and seems to withdraw when her family is being celebrated.

Mirabel’s emotions are relevant and adolescent. She is old enough to be mature about her pain but young enough that she seeks validation to know she belongs in her world, that she aims to be helpful to feel a purpose in the family. As Mirabel risks and rebels to save the family magic, we start to appreciate her for doing something other than sulking or being pointlessly proud of the Madrigals. She is the demure and neglected girl who becomes her boss and makes sure that her family appreciates her, a brown feminist role model for an audience who may feel cheated by society and circumstances.

Still, isn’t it a problem to tell girls that they have to make a significant contribution (because Mirabel’s is sometimes shown as the only important function in the family) to overcome that trope of un-necessity that comes with being a girl, POC, or overlooked in general? Can’t it perpetuate that pressure on brown people to be useful, live up to societal standards and excel just to be accepted? Why can’t Mirabel feel worthy for just riding her wave and facing her obstacles, as with movies like “Frozen”? This girl-with-a-purpose is also seen in the Polynesian “Moana,” emphasizing the protagonist saving her entire people. Why not give them lovers and petty involvements instead? Or would that be a poorer step in good representation?

This is admittedly just a Disney movie whose intent is to showcase a teenage girl who defies her restrictions, contributing to needed representation in mainstream media and giving us vicarious accomplishment and festive spirit. There is also a pleasant Latino representation in Bruno, a 20-something Madrigal who isolates himself from the family he loves to protect them, is a manifestation of the self-sacrifice sometimes expected of minority children for their families.

Despite its heavy topics of belonging and dispossession with sentimental heritage themes, “Encanto” is also an easy watch; all its characters are funny and sweet, making jokes out of painful subjects. A town girl once suggests to Mirabel that she lacks magic: “Maybe your gift is being in denial.” Thus we are assured that the take-away isn’t only in analyzing Mirabel’s moods and denouncing colonialism but especially in the film’s nonstop undertone of community, support and healing.

Your donation will support the journalists of Hill Top Times and RH Media. Your contribution will help cover travel and registration costs needed for state and national conventions.

Nanditha is a senior and second-year staff member at Hill Top Times.