We show students Anne Frank’s diary and tell them she dreamed of becoming a writer. They read her words, witness her fears, and follow her story from hiding to heartbreak. We show images of Auschwitz, assign “Night” by Elie Wiesel, and examine Nazi ideology with emotional depth and moral clarity. Holocaust education doesn’t shy away from horror. We teach about gas chambers, ghettos and genocide because the truth demands it.

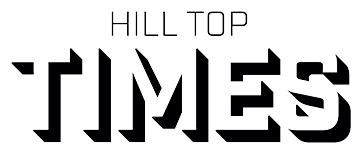

But when we teach slavery, we rarely name the people. We don’t talk about the little girl sold away from her mother, or the man whipped so badly his scars formed a map. We reduce a 400-year atrocity to an economic system and a major cause of the Civil War. Students learn about plantation economies and the 3/5 Compromise, but not about the millions who were sexually abused, branded, auctioned as children and treated as livestock.

The result is a curriculum that treats slavery as background noise rather than a violent, human reality that shaped the nation’s foundation and has undeniable effects today.

First-person accounts of slavery do exist—Frederick Douglass, Harriet Jacobs, Olaudah Equiano, the Works Progress Administration’s “Slave Narrative Collection”—but they’re often sidelined or sanitized. Moreover, there’s no shortage of age-appropriate historical fiction that can foster the same empathy and humanization—books like “Copper Sun” by Sharon Draper offer emotionally vivid windows into enslaved people’s lives without compromising the truth.

We prioritize emotional connection in Holocaust education because it cultivates empathy. We need to do the same for slavery. If we demand rigor in telling the stories of genocide victims, we owe that same rigor to the victims of slavery—not to traumatize, but to tell the truth. Research shows that specific stories—like Equiano’s kidnapping or Jacobs hiding in an attic for seven years—activate moral reasoning and understanding far more than general statistics and facts.

This is especially urgent today. State policies like Texas’s HB 3979 and SB 3 restrict how slavery and racism can be taught, and euphemisms like “involuntary relocation” have been proposed for second-graders. PragerU videos distort history, with cartoon Frederick Douglass suggesting slavery taught work ethic and was a “compromise.” Even federal institutions like the National Park Service have recently reframed the Underground Railroad as “Black/White cooperation,” erasing Harriet Tubman and the violence of the Fugitive Slave Act.

Schools must resist this patriotic mythmaking and erasure. Diluting slavery’s horror robs students of the tools to understand the present. Without grasping the violence of the past, how can they contextualize redlining, voter suppression or mass incarceration? How can they recognize microaggressions as part of a long legacy of dehumanization?

Some argue graphic content may traumatize students. But “age-appropriate” doesn’t mean sanitized. Young children can learn about enslaved people’s resistance and survival. High schoolers can analyze slave codes that legalized rape, illiteracy, and dehumanization and read accounts of those affected.

Discomfort is necessary. History is uncomfortable. Humanity is uncomfortable. If we protect students from the truth, we protect injustice from scrutiny.

Teaching slavery the way we teach the other atrocities isn’t just a curriculum choice. It’s a moral obligation. Students deserve more than vague references and euphemisms. They deserve stories. They deserve truth. And slavery deserves to be taught with its full, human weight—not just as history, but as humanity.