“Go buy cute winter boots to protect you from ice!”

At first glance, the phrase seems like a mundane call to bundle up for the winter. But on TikTok, it takes on a different meaning. “Cute winter boots” is another example of “algospeak,” where social media users use coded phrases to bypass censorship and discuss sensitive topics on moderated platforms.

When users say “cute winter boots to protect you from ice,” or use the “#cutewinterboots” hashtag, they are referring to resistance against U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE). However, the phrase has grown to be a more general symbol of political resistance.

In these TikTok posts, users often hold up papers with information or calls to action, and the comment sections fill with rally crying like “deny, defend, depose” and “eat the rich” woven subtly into unrelated words.

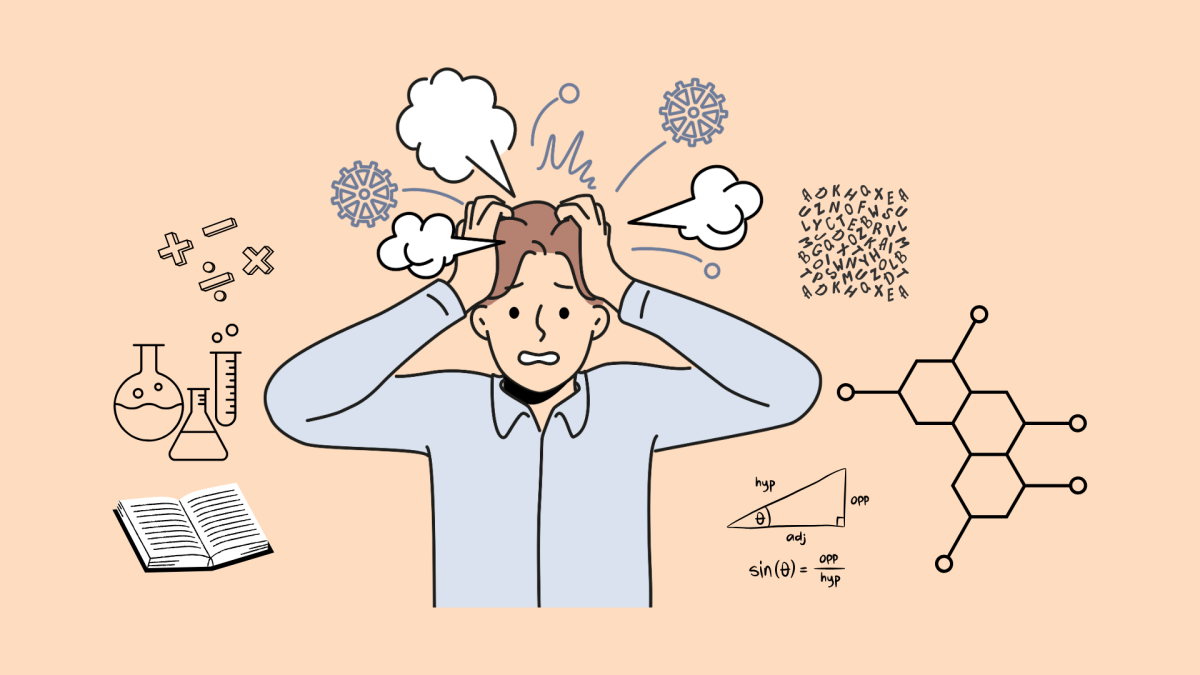

But with its rise has come familiar backlash—criticism that often lumps all online activism together as performative, claiming that users are “cosplaying revolutionaries” from the comfort of their bedrooms. Many draw comparisons to the Black Lives Matter’s (BLM) Blackout Tuesday trend in 2020, where people flooded Instagram feeds with black squares, a gesture that many felt was empty and vain.

While such criticisms have merit, dismissing “cute winter boots” as just another act of “cringe” and “useless” digital slacktivism misses the bigger picture. Online “performative” activism, while flawed, has significant value in raising awareness. Nevertheless, it should be complemented by more substantial action.

Consider the BLM movement. During the COVID-19 pandemic, it was full of what is deemed as “performative activism”—from the black squares to Instagram highlights to profile picture changes. Yes, some of these were performative. Yes, some people posted them just to fit in. But at its peak, public awareness of police brutality had significantly increased.

The same potential exists for TikTok trends like “cute winter boots.” A single video surely won’t dismantle ICE as participants want, but it might introduce someone to an issue they’ve never considered before. I, for example, learned more about deportation policies because of these posts.

While online, performative activism can be influential, it is also inherently limited. Sharing a post, commenting on a video, or blasting a protest song on TikTok isn’t going to reshape policy. And it’s true that for many, that’s where their activism starts and ends. But movements don’t always need everyone to be on the frontlines—sometimes they just need people to pay attention.

Online activism has the potential to reach and influence a wider audience, particularly those who might not engage with traditional forms of activism. Historically, many political movements have been fueled by communication shifts, like pamphlets in the American Revolution, newspapers in the Civil Rights era, or Twitter in the Arab Spring. Online activism isn’t a replacement for direct action, but it is an entry point, and dismissing it outright ignores how activism evolves. Moreover, criticizing online activism too harshly can push new or curious individuals away from activism altogether.

That being said, no revolution has ever been won with aesthetics and slogans alone. Real change requires organizing, political participation, and direct action.

Social media has lowered the barrier to entry for political engagement. That’s not a bad thing. But awareness is only step one. The challenge now is to ensure that the momentum doesn’t stop at cute winter boots.